(These are the opening remarks I gave at ‘Marxism in Motion: The Intellectual History of Marxism in and about the Global South during the early Twentieth Century’, a workshop at UCL on Friday 22nd September organised by Peter Morgan and Tanroop Sandhu.)

Good morning and welcome, everybody, and before I start I would like to extend my thanks to the organisers for the invitation to speak on some of the broad themes of what is set to be a fascinating and important workshop today. By way of introduction, I should say that there are three strands of my research which tie into today’s areas of inquiry: first, the various political manifestations of Marxism in Mexico; second, the growth of diverse and shifting radical networks in North America and the Caribbean in the pre-war period, comprising labour, cultural, and political figures and organisations; and third, the dynamic between socialist and indigenous political identities. As you can imagine, then, I was very excited to see the programme that Pete and Tanroop have put together and to hear what you all have to say. What we will hear about, I think, is heterodoxy in a time of supposed orthodoxy. This won’t be a surprise to any of you, but one still finds traces – more than traces, actually – of the received wisdom that Marxism came late to the Global South, and was imposed from without. From critics, who derided Marxism as an ‘exotic doctrine’, this was often an effective narrative to perpetuate; for so-called ‘second world’ powers with international ambitions – first the Soviet Union, later China and Albania, and arguably Cuba, though I think the latter fits into a different category – the role of saviour-from-without had some political attraction (though I must say, this usually waned fairly quickly after gruelling armed conflict – but that is rather after our period). Many histories of Marxism make reference to the Lenin-Roy ‘theses’ or debates, but the broad characterisation is that the International parked the colonial question, or fudged it. What historians of the left in the Global South recognise, however, is that these debates were not parked – they were vibrant, lively and impactful discourses, and in many places went far beyond intellectual struggle and into the temporal realm.

Among the papers we will hear today, there are many foci: Marxism’s interactions with other ideological and religious traditions; national and colonial questions; Marxism and feminism; and challenges to Eurocentric models of capital-labour dynamics, inter alia. Incidentally, fitting these interactions into some sort of schematic was something I dabbled with (admittedly in a rather unsophisticated way) during my doctoral research almost fifteen years ago.

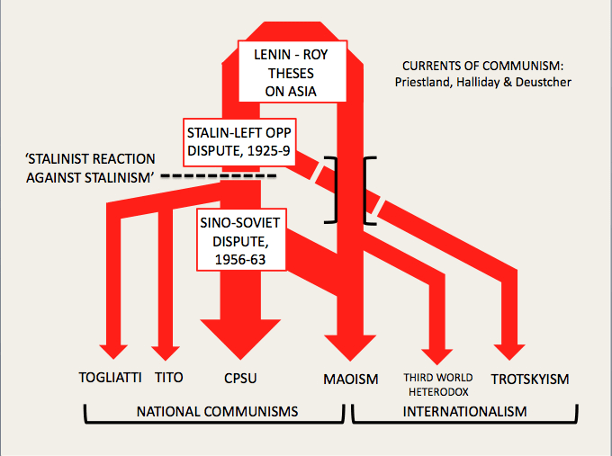

This is a diagram I made at the time – I don’t think it would be nearly as simple if I revisited it now, and I was still sticking to a simple one-dimensional continuum of nationalism and internationalism, which I don’t think holds up, but I thought you might be interested!

I think we can bring these together in three categories which of course spill out far beyond the confines of our discussions today.

The first is state forms, which pervades discussion of Marxism as it relates to nations, empires, and colonies. State forms are dynamic across time and space, and particularly in the twentieth century were a site of conflict within Marxism but also in the broad geopolitical order. I suppose the key question here for political activists in countries of the global south was balancing the risks and rewards of riding two horses at once: the pursuit of a sovereign, autonomous nation state, and the pursuit of socialist political economy. In terms of anticolonial conflict or potential conflict, the former might be characterised as a tactical approach within the broader strategic goal of achieving the latter. However, as numerous scholars, activists and Marxist thinkers have noted, the nationalist horse has very often proved faster and stronger, bullying its socialist counterpart off the track, or at least leaving it limping behind. Does a focus on state forms necessarily relegate political economy to the margins? Again, this has been something I have – perhaps unwisely – tried to schematicise in the past.

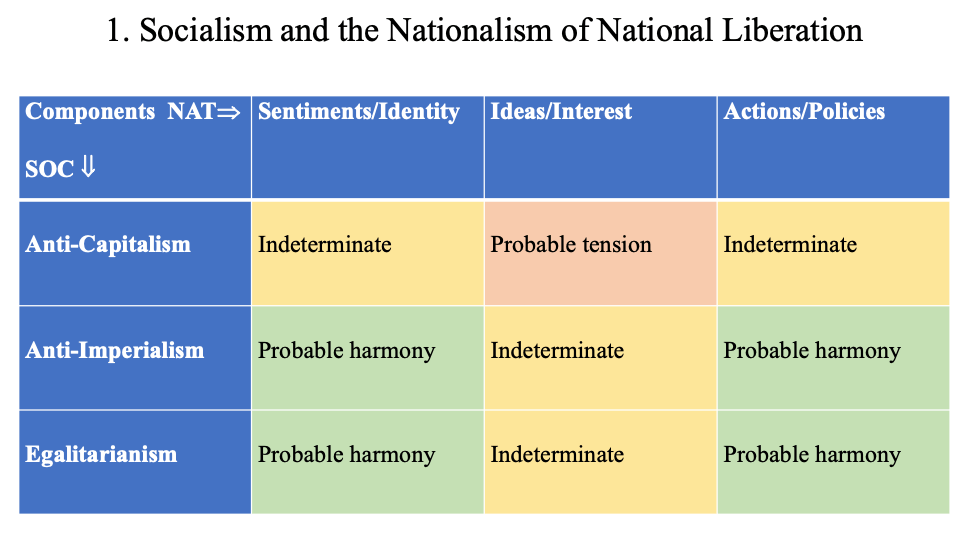

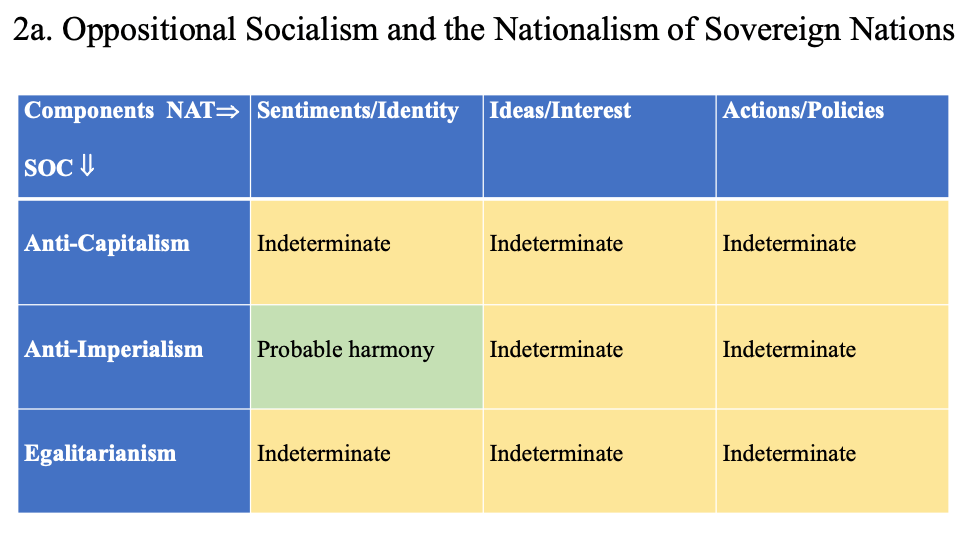

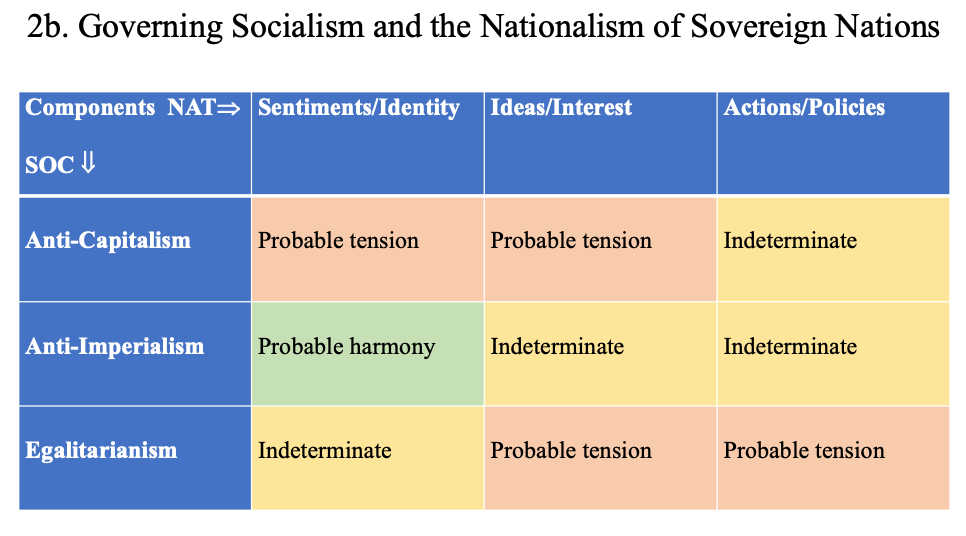

Taking Breuilly’s view (via Morris) of nationalism as comprising sentiments, ideas, and actions, and using a definition of Marxist praxis which encompasses anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism and egalitarianism, to my mind there is considerable potential overlap between socialism and movements of national liberation. Indeed this is such a common feature of twentieth century anticolonial struggles as to be rather cliched. What is also rather cliched, unfortunately, is the extent to which this potential overlap unravels upon achievement of the nation state and particularly when socialists come to govern these new entities.

I don’t want to get too bogged down in this because of course the differences between case studies depend on a vast range of factors: factionalism, alliances, ethnolinguistic composition, class structures and so forth. However, I just wanted to restate the many ways in which nationalism can turn in to a bucking bronco, to return to my horse metaphor.

A second category would be that of capital and labour forms. Many orthodox European or European-influenced Marxists adhered to a particular schematic – some would say dogmatic – model of socio-economic change. Confronted with self-evidently unfamiliar capital-labour relations in various parts of the world, these orthodoxies could lead to two outcomes: the first, an assignation of feudal status to regions, sectors, groups of people and so forth – this was frequently the case with the Mexican Communist Party, for instance; the second being quixotic attempts to speed up the anticipated social change, to make peasants think like proletarians. This latter approach is perhaps more closely associated with liberalism in Latin America at least, but such mass social engineering had appeal to many Marxists working in health, education and infrastructure too. A third approach, though, was heterodox (and by its nature rather different depending on its context): to take Marxism as a starting point, as a framework, even as a guide, but to give equal importance to local material (and even spiritual) realities. Thus where orthodoxy could either say ‘there are no proletarians here’ or (less frequently) ‘we can turn these people into proletarians’, heterodoxy worked with what it had: ‘these people have reasons to revolt, to become socialists’.

A third category is that of social forms, including the consideration of race and gender and their relationship with socialism and capitalism. Some questions of identity which are raised here also relate to state forms and capital-labour forms of course – particularly on the so-called ‘colonial question’. While much of the conventional literature sees the integration into Marxist thought of identities beyond class as process beginning only in the 1960s, we will see today that it has important antecedents in preceding periods. There are of course plenty of accounts of debates within European Marxism on the questions of women, colonies, ethnicity and so forth, but they sometimes unwittingly perpetuate the ideas that a) Europe was the only place such debates were happening or b) Europe was the most important place such debates were happening. I don’t think we will get that impression today.

To conclude my contribution, I expect the papers presented today to show Marxism as a starting point for a wide variety of contextual discourses, with groups and individuals using that ‘prompt’ to create a multiplicity of responses to local material circumstances and prevailing ideological currents. Hence my titular analogy: Marxism in the first half of the twentieth century was a vast and expanding ocean, but where it made landfall we find many and various coasts, and in these places the land and sea shaped each other in fascinating ways.